Those in power are terrified of peace.

By Michael Nagler

First published at Waging Nonviolence with light editioral support from WNV team.

Sometime in the mid 1950s a dramatic version of “The Diary of Anne Frank” was performed in Berlin. When the curtain went up, nobody moved. The audience was stunned. It was too soon after the event. The horror of Nazism had ended, but signs of it could still be seen everywhere. For most Germans, the wound was too raw.

When I was in Heidelberg some 40 years later, I attended a reading by novelist Jakov Lind, who had hid out and barely escaped detection as a Jew in the Netherlands and even Germany itself right through the war. His talk was all about literature and he never mentioned his harrowing experience (which I appreciated), but at the end of it one of the German students, prodded him, “Tell us how it was under those Germans (unter den Deutchen).” As I recall, Lind didn’t take the bait; but what stood out for me was that student’s attempt, perfectly understandable and perfectly legitimate, to radically disassociate himself and his generation from the still fairly recent atrocities.

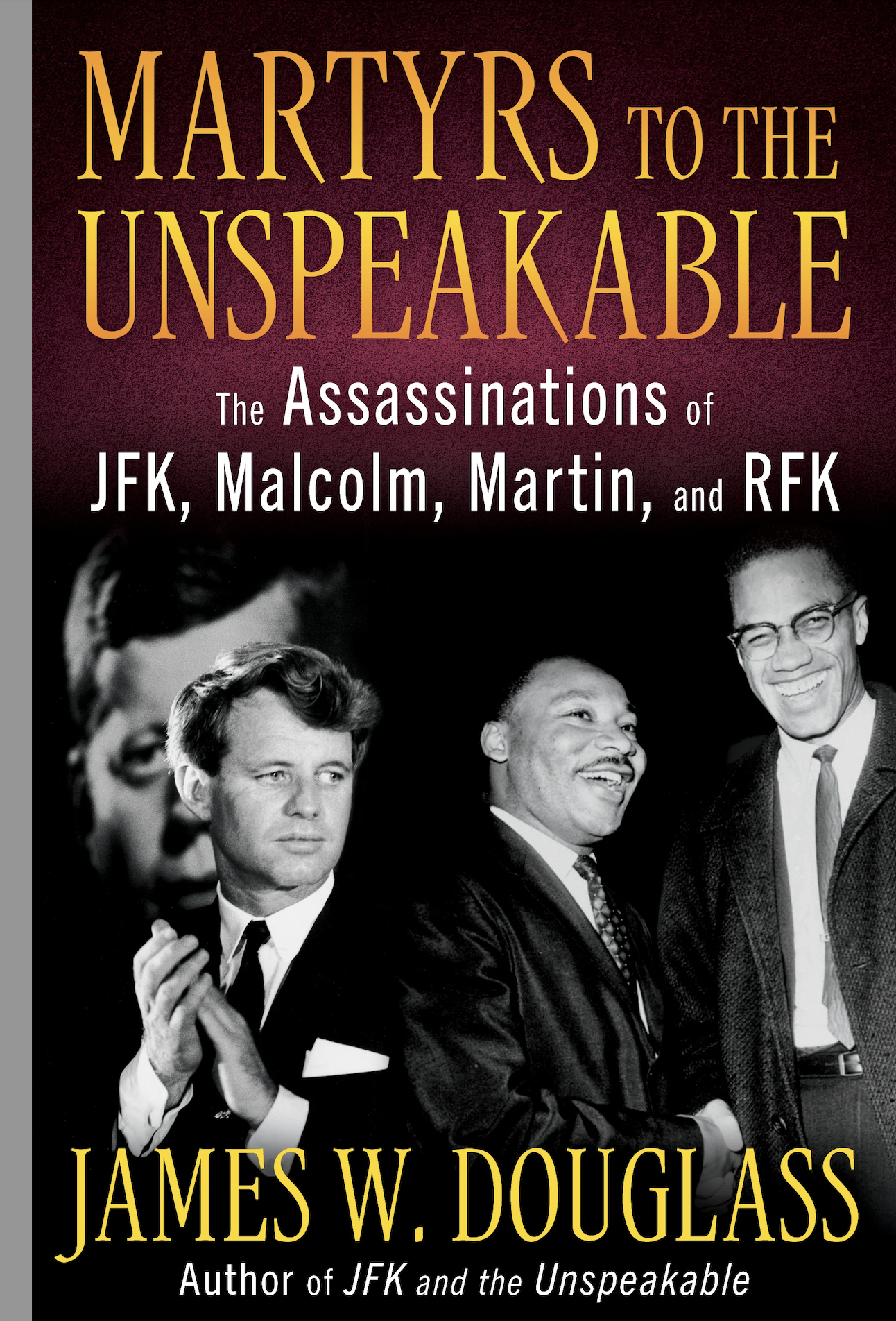

There are elements of this situation that may be useful for us today. After all, if we are perfectly truthful, we have some atrocities of our own. I’m thinking not so much of the climate situation, which receives most attention, but of the revelations in a recent book by my friend Jim Douglass, “Martyrs to the Unspeakable,” about the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcom X. Summing up his recent interview with Douglass about the book, Robert Ellsberg concluded that the four brutal assassinations were done, “to strike down those whose message of peace and justice threatened the national security state.”

I would say that even “justice” is secondary. King, for example, did a great deal for racial justice, but he was not killed until one year to the day after he gave his powerful speech denouncing the Vietnam war at Riverside Church in New York. JFK likewise was most probably killed because of his famous overture of respect and cooperation with Khrushchev (imagine what that cooperation could have done for the world!).

And in a lighter, but still quite cogent vein we might consider the satirical “Report From Iron Mountain” by Leonard Lewing in 1967, depicting the “threat” of peace to the prevailing order — i.e. the national security state. This book was protected from being taken too seriously by fantasy and humor. It’s a time-honored method: think of the fables from Aesop to la Fontaine. But it makes the very serious point that everything from our economy to the sense of meaning for many people depends on war. The elite who control the present order, be they in government, the military, or indeed in crime, are terrified of peace.

Place in juxtaposition to this dark fact the observation of St. Augustine in “The City of God,” where he wrote that “even on the level of earthly and temporal values, nothing that we can talk about, long for, or finally get, it’s so desirable, so welcome, so good as peace… Peace is so universally loved that its very name falls sweetly on the ear.”

We thus find ourselves being in the grip of a group of people who are driving civilization in the exact opposite direction of our deepest longing. They are able to wield power far out of proportion to their small number by controlling the narrative that controls the thinking of the majority. Hence they are controlling our destiny; as the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, a text from ancient India, declares, “as our thought is, so is our deed; as our deed is, so is our destiny, whether good or ill.”

If all is not lost, it is because as William Cullen Bryant said, “truth crushed to earth will rise again.” That is, there is an inherent power in truth that will come out at some point, even if we’ve done our best to conceal it. And of course, men acting against their own best interest are far more vulnerable than they may appear. In Shakespeare’s “King Lear”the villainous Edmund says, “Where I could not be honest, I never yet was valiant.” This tension is in fact showing up in a phenomenon for which we have now a name and scientific evidence: “moral injury,” the internal harm we cause to ourselves when we harm others.

And perhaps therein lies the profound secret: there are no “others.” To convince ordinary people of this profound truth would take a complete change of paradigm. Such a sea-change is not impossible; it has happened before, and I recommend that we find ways to do this, whileat the same time implementing more short-term, practical measures to raise the human image and human understanding so that such atrocities become less and less thinkable.

After all, we will be drawing upon the fundamental reality of our very nature, identified by Augustine and mobilized, in our own time, by Gandhi. We know that people can rise up in large numbers in the face of emergencies, and not just to protest but to rebuild, to help others even at some risk to themselves (see Rebecca Solnit’s book “A Paradise Made in Hell”).The question is: How do we make people aware that we’re in an emergency?

I maintain, paradoxically, that we can do so by making us aware of the sanctity of life and the dignity of the human being. In our part of the state, billboards appeared not long ago with pictures of U.S. vessels bristling with cannons and the slogan, “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Those Who Would Threaten It.” In other words, forget happiness. I say, No! Seize happiness — but know that it doesn’t come from inflicting suffering but from relieving it, not from alienating but uniting. In other words, from knowing what it is to be a human being.